How The Days Leading Up To King’s Funeral Played Out In Atlanta

In My List

In My List

In the days after Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, riots broke out in more than 100 cities across America. More than 50,000 National Guard troops – the largest domestic military deployment since the Civil War – were mobilized around the country.

But King’s hometown of Atlanta avoided the unrest. Why did the city remain peaceful as it prepared to host the civil rights leader’s funeral on April 9, 1968? Disparate groups in the city all played a role.

“It was all hands on deck, even though they had different motivations,” said Rebecca Burns, whose book “Burial for a King: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Funeral and the Week that Transformed Atlanta and Rocked the Nation” gives a detailed account of those days. “Everyone was jumping in and doing their piece.”

Churches opened their doors to feed and sleep some of the nearly 150,000 people flocking to Atlanta. For many white churches, it was the first time they had black people in their sanctuary. At the city’s historically black colleges, student leaders trained their fellow students on how to be parade marshals to help with crowd control.

Burns, whose book had its roots in a story she wrote for Atlanta magazine, said that avoiding violence was Mayor Ivan Allen’s top priority. He ordered police placed on two 12-hours shifts each day while detectives walked the streets around the clock.

As the hot spring day began, uncertainly still hung in the air. Gov. Lester Maddox, who earlier had refused to fly flags at half-staff before being ordered to by the federal government, lined up state troopers around the State Capitol, with orders to kill any protester who stepped on the grounds.

Services began with a small memorial at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where King and his father served as co-pastors. Among those packed into the chapel were the four candidates for president in 1968 – Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, Eugene McCarthy, and Robert Kennedy (who would himself be assassinated two months later) – along with civil rights leaders including Thurgood Marshall, Andrew Young and Jesse Jackson and entertainers and athletes like Harry Belafonte, Wilt Chamberlain and Jim Brown.

One moment in particular struck the mourners inside the church and the thousands listening outside: the sound of King’s own voice. Two months before he was killed, King delivered a sermon at Ebenezer where he imagined his own funeral. Now a recording of those words rang through the church’s speakers.

King asked that rather than talking about his Nobel Peace Prize or hundreds of other awards, he’d like someone to mention how he “tried to give his life serving others,” “to feed the hungry” and “tried to love and serve humanity.”

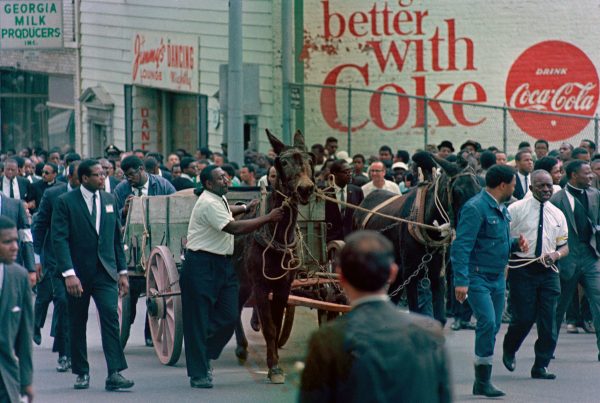

After that service, King’s casket was loaded onto a mule-driven wooden farm cart as a striking symbol of his commitment to the impoverished in the Poor People’s Campaign, a demand for economic justice. The cart then began a three-mile journey through Atlanta’s streets to a second memorial, this one at King’s alma mater, Morehouse College. It was, at that time, the largest funeral for a private citizen in the United States.

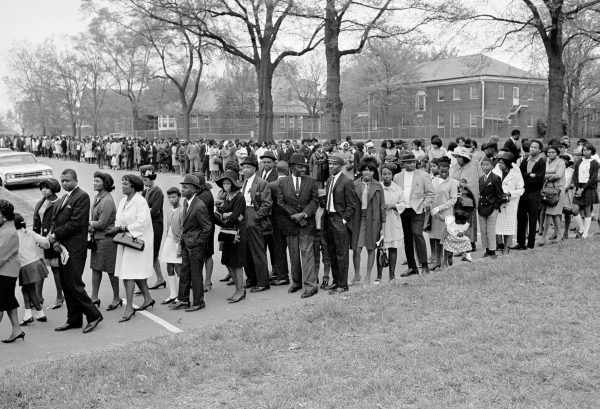

An estimated 50,000 people lined the sidewalks, crammed onto hillsides and park benches and even hung from streetlights to catch of glimpse of the procession. And there was only quiet. In that hush, people could hear the clop of the mule’s hooves on the pavement.

Although his body was later moved to a marble sarcophagus at the King Center, King was buried that evening in South-View Cemetery, about five miles south of downtown. His headstone echoed the words of his most famous speech, “Free At Last! Free At Last! Thank God Almighty, I’m Free at Last!”