How The Media Covered Martin Luther King Jr.’s Assassination In 1968

In My List

In My List

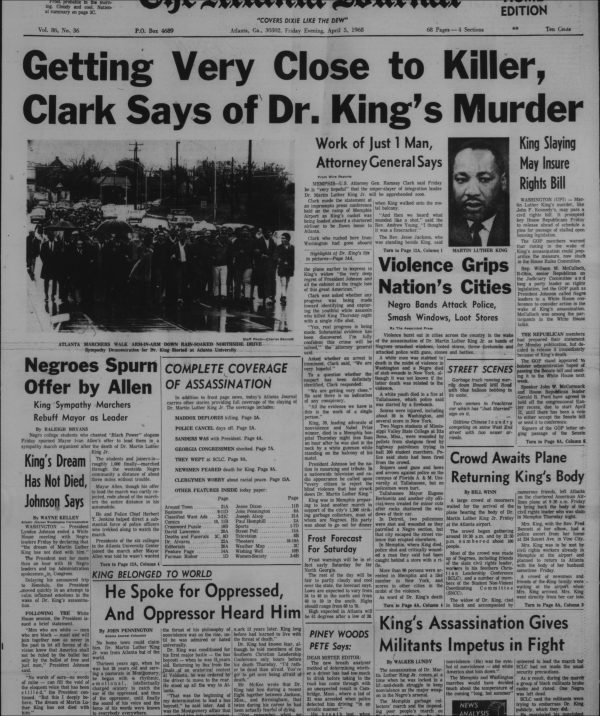

On April 5, 1968 — the day after King’s assassination — newspapers reported the news using large text and photos of King, his family and the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn.

The story of King’s assassination made the front pages of publications printed all over the United States, and his impact reached many around the world.

In addition to news reports and updates on the event, newspapers also ran editorials denouncing the assassin’s deed and calling for peace.

Reporting On The Reactions

“Crowd Awaits Plane Returning King’s Body” proclaimed The Atlanta Journal on its front page April 5, 1968. Around 100 mourners had gathered at the Atlanta airport to wait for King’s body, according to the story. The Atlanta Journal also ran a story about Republicans pushing for civil rights legislation in the wake of King’s death.

Mentioning that King was Nobel Peace Prize winner, The Atlanta Constitution reported on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s response to the murder, the curfew that was imposed in Memphis and a police bulletin for a “young, dark-haired white man” who was seen fleeing the scene in a car.

Both publications also noted the riots that took place across the country.

“Violence Grips Nation’s Cities” was a headline that appeared in The Atlanta Journal on April 5, 1968. The corresponding story was attributed to The Associated Press and reported on three deaths and numerous injuries that might have been related to the riots that took place around the country.

The Atlanta Constitution ran its own front-page story reporting on a fire that was started in a grocery store at Fair and Ashby streets in Atlanta and that a window of a car parked by the civic center had been smashed by a brick.

“There are a lot of editorials like pleading for calm, you know, that the nation should remain calm during this tragedy,” said Kat Wilmot, a print news archivist at Washington, D.C.’s Newseum, which opened a new exhibit this year that looks at the tumultuous events that surrounded King’s death in 1968.

“And especially, they talk about President Johnson’s speech about rejecting blind violence and that Dr. King wouldn’t want violence to occur, because he was so against that.”

As Time Passed

The conversation continued in the media months after King’s death. Newspapers kept readers updated on the search for James Earl Ray. The Associated Press reported on his going to jail and details about a room he allegedly rented in Canada.

The editorials continued as well. Students and professors used campus newspapers to address racial segregation and discrimination in their universities.

A Mercer University student named Gary Johnson wrote multiple columns in his college’s student newspaper, the “Mercer Cluster.” On April 23, Johnson’s column addressed racial segregation on his campus and demanded quick change.

“During the past several weeks, the phrases, ‘I have a dream!’ and ‘We shall overcome!’ have echoed throughout this nation,” Johnson wrote. “And in reply the phrases echoed back have been, ‘Give us time to adjust!’ and ‘Wait!'”

Johnson asked, why should black Americans wait for something they should already have? Johnson quoted King in another editorial that was published on May 24, 1968.

Two political science professors at the University of Georgia, William O. Chittick and Michael Cohen, wrote about polarization in the student newspaper, “The Red and Black.” Their co-authored editorial appeared in the April 18, 1968 issue.

“We call upon the University of Georgia community — its students, faculty, staff, administration, and all the organizations which are a part of it — to become more active in helping the struggle of black Americans to attain equality of resources and opportunities,” they wrote.

“Only time will tell if Dr. King’s death was in vain, but time will run out quickly.”

Connections To Today

Patty Rhule, a founding editor of USA Today and the director of exhibit development at the Newseum in Washington, D.C., said reporting on King’s death was reflective of the makeup of newsrooms in 1968.

“If you think about it, who was in charge of the mainstream newspapers and publications? Um, white guys!” Rhule said. “There weren’t a whole lot of women in newsrooms at that time. Certainly not a whole lot of black Americans in newsrooms telling their story.”

“How could stories of what life was like under segregation, under racism, be told if you did not have people who are experiencing those stories on your staffs?” she added.

Rhule also said a lot of the issues of 1968 find similar parallels today.

“It was kind of amazing when we were researching this (1968) exhibit, when we saw the things that people were protesting for: economic injustice, mistreatment of African Americans by police — all those things — you know, human rights,” Rhule said.

“Fifty years later, we’re still dealing with some of the same issues.”