In 1960 Speech, King Encouraged The Women Of Spelman To Take Action

In My List

In My List

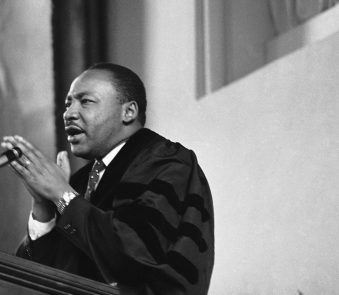

On April 10, 1960, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed Spelman College as guest speaker for its 79th annual Founder’s Day.

For 31-year-old King, who had a growing national profile, returning to Sisters Chapel on the leafy quadrangles of Spelman’s southwest Atlanta campus was like a homecoming. In fact, he noted in the typescript of his speech, he had often visited the chapel as a member of the chorus and glee club at nearby Morehouse College.

“I happen to be a Morehouse man and Morehouse men always consider it a privilege to speak to Spelman ladies,” King told the audience.

Founded in 1881, Spelman is the nation’s oldest historically black college for women, and its ties to the civil rights movement and its iconic leader run deep.

Spelman’s History Of Activism

Five generations of King women have attended Spelman, according to school records. Among them are King’s maternal grandmother who was a student at Spelman Seminary in 1888, his mother who graduated from its secondary school in 1922 and his youngest daughter, the Rev. Bernice A. King, who graduated in 1985.

King made his Spelman speech titled, “Keep Moving from This Mountain,” at the dawn of the student sit-in movement. It can be interpreted as a call to fight racial segregation. While it didn’t spark the student movement in Atlanta, it did ripen the environment for demonstrations.

Spelman, in some ways, was an unlikely location to call for a revolt. Two white missionaries with financial backing from northern philanthropies founded it and generations of students were expected to embody the white-gloved gentility of their New England Puritan forbearers. A black woman would not lead the institution until 1987.

Though progressive for their era, administrators did not so much question Jim Crow as they did teach students how to thrive within its barriers, according to late Spelman sociologist Harry Lefever’s book “Undaunted by the Fight: Spelman College and the Civil Rights Movement, 1957-1967.”

Things began to change in the 1950s and 1960s, however. Howard Zinn, a history professor and controversial social activist, who was white, encouraged his students to test Georgia’s segregation laws as early as 1956, according Lefever’s book.

‘We Were Determined’

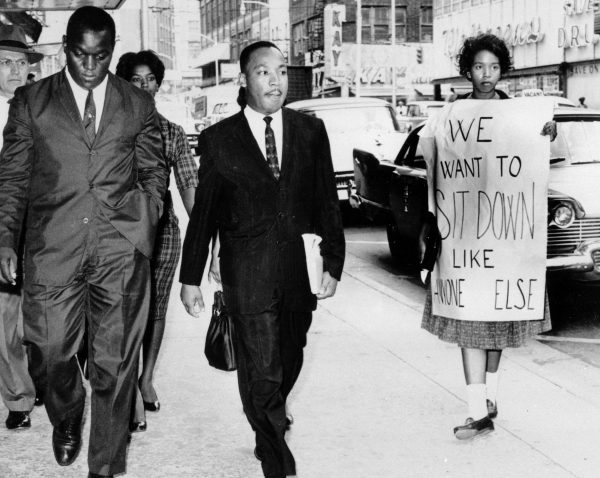

On March 9, a month before King’s speech, Atlanta newspapers published a manifesto by student activists from affiliated institutions of the Atlanta University Center, which called for a nonviolent end to segregation. Titled, “An Appeal for Human Rights,” it received national attention and much of it was written by Rosyln Pope, class of 1960.

“We were ready to do what we needed to do to try to bring about a change in the status of our humanity,” recalled Pope, 79. “We were determined we couldn’t go on as we were.”

The first wide-spread sit-in demonstrations in Atlanta happened six days later. More than 70 students were arrested, according to historical accounts. In the demonstrations that followed, Spelman often produced the most students of participating institutions, Pope said.

Against this backdrop, King told the Founder’s Day audience that the burgeoning student movement was “one of the most significant movements in the whole civil rights movement.”

“For you students, along with other students all over the nation, have become of age, and you are saying in substance that segregation is wrong and that you will no longer accept it and adjust to it,” he said.

“I have faith in the future because I have faith in God and I believe that there is a power, a creative force in this universe seeking at all times to bring down prodigious hilltops of evil and pull low gigantic mountains of injustices.”

For the young women who peered up at King, his message was encouraging, said Richard Benson, a Spelman professor who studies black student activism.

“I think this had so much to do with reassuring young women at this time that they too are needed,” he said.

Racial tensions continued in the months following the speech.

Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, a second generation Spelmanite who participated as a senior in the October 1960 sit-in at Rich’s department store, remembered rules for attending chapel daily, following a dress code and adherence to a strictly enforced curfew.

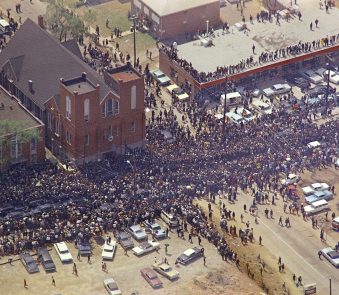

On Oct. 19, widespread sit-ins occurred at Atlanta businesses. Among the dozens of people arrested, including Challenor, was King, whom students had encouraged to participate to garner attention.

“You could not listen to Martin Luther King and not get moved,” remembered Challenor, 79, who like other students often visited Ebenezer Baptist Church to hear King preach. “It was like a train. He’d start off very slowly and then speak more quickly and with greater intensity. It was just amazing.”

Following King’s assassination in 1968, King’s body lay in state at Spelman’s Sisters Chapel for twodays before his funeral.

April 4 will mark the 50th anniversary of King’s assassination.