How Students In Atlanta Learn About Dr. King Today

In My List

In My List

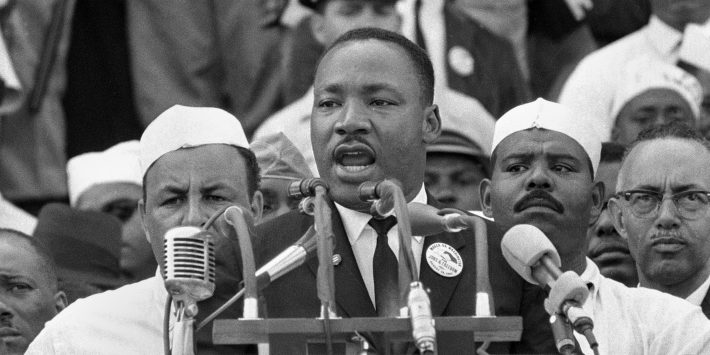

Children across the country learn about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in school. Often, it’s around his birthday in January and usually includes something to do with his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Children and teens understand Martin Luther King Jr. was an important figure in America’s history but teachers in King’s hometown of Atlanta, like Jennifer Gonzalez, are furthering the richness of their curriculum by going beyond the Georgia Performance Standards requirements.

Gonzalez has been a teacher at Decatur High School in DeKalb County for 10 years. She was always fascinated by the intersection of race and gender specifically during the equal rights movement, which led her to pursue her Masters in History from Georgia State University.

This same spark is what keeps her students engaged in the classroom today.

“We are prescribed what is in the Georgia State Standards. Because we have an end of course test and that is the law so that is what we have to teach. Theoretically, the standards are a starting point and should be the minimum students learn,” Gonzalez said. “I find especially when you’re talking about African-American history there is a lot more richness that can be found in the standards.”

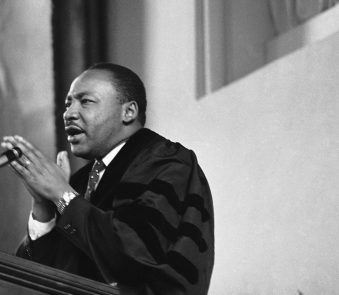

The high school standards for King are limited to the Letter from Birmingham, the “I Have a Dream” speech and his 1968 assassination.

While these are monumental periods in our history, it only scratches the surface of the importance of his role in the civil rights movement. Gonzalez incorporates visual factors in her lesson by showing the documentary “Eyes on the Prize,” which allows her students to see footage from the time period which she believes is a powerful learning tool.

Gonzalez isn’t the only teacher broadening her lesson plans. Cassi Beach, a kindergarten teacher at Peyton Forest Elementary School in Fulton County, celebrates the life of King with her students before the national holiday in January.

“If you look at Georgia Performance Standards they are very surface level. I do my best to go a little deeper for my students to understand why Martin Luther King Jr. was so important and that the kids need to know not only who he is, but the reasons why and the bigger idea to push their thought processes,” Beach said.

Beach starts the day reading and discussing two books with her students, “The Watsons Go to Birmingham” and “The Story of Ruby Bridges.” She explains to her students that although segregation was over, people were still not being treated with respect based on the color of their skin and ties in why King was so important. They finish the day by watching the the “I Have a Dream” speech.

“We pick apart the speech and explain why King’s legacy was so important and why it’s good for the students to speak up. Most of them remember he died, but I try to reiterate his words, memory and ideas that will go on forever,” Beach said.

Black History Month is generally isolated to a few notable historical figures when it’s being taught in schools, but Gonzalez encourages her students to broaden their education and look at people who inspired King, voices like Septima Clark and Ella Baker. This process allows her to use King as a launching point for lessons about anti-war protests and the women’s movement because Gonzalez believes King’s teachings and legacy don’t end with his death.

“We don’t isolate teaching African-American history to February. I have a wall outside of my classroom where students put positive images of African Americans throughout history. It starts mostly right after the Civil War and we add to it all year long and celebrate it in February. There’s a difference between learning history and celebrating something,” Gonzalez said.

There’s a pattern of civil disobedience dating back to the teachings of Henry David Thoreau read by Gandhi and then read by King creating a pattern which can be tied into current events surrounding Black Lives Matter, Confederate statues and the National Football League.

“If we can keep sharing and showing them examples of the various ways you can be a good person; the Black Panthers, Stokely Carmichael, Marcus Garvey – there are so many options to help them decide which direction they feel is most productive or helpful and resonates with their personal experiences or philosophy. They get to see all kinds of positives and not just a singularity. That all goes back to Dr. King because if we just see him as someone who was marching for voting rights that’s such a limited view of who he was and how much he contributed,” Gonzalez said.

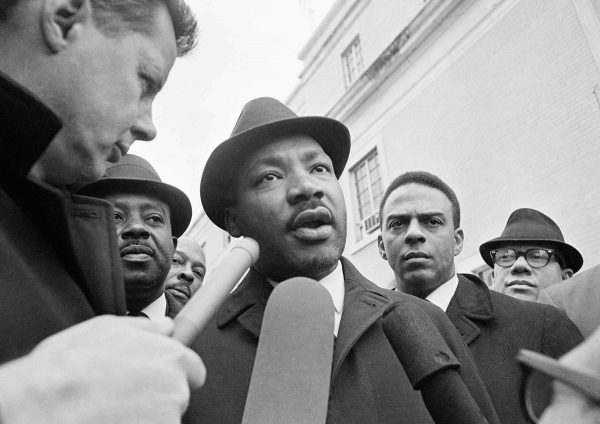

Charles Elliott, a student at Kennesaw State University, is studying to earn a Masters of Science in Conflict Management and has spent the last six years studying nonviolence. Elliott speaks about the ideas King borrowed from Johan Galtung, a popular peace theorist who was the first academic to speak about nonviolence.

“Martin Luther King knew a ton about the injustice of the prison systems and he talked about it all of the time. He spoke about black men and women being jailed and put behind bars for no real reason at all besides the color of their skin,” Elliott elaborated.

In the letter, King writes to his colleagues in Atlanta from Birmingham he writes, “In any nonviolent campaign there are four steps; the collection of facts to determine whether injustice exists, negotiation, self-purification then direct action.”

These four steps are what the Conflict Management Program at Kennesaw State University is built on. Identifying injustice through data. Negotiation. Self-purification — identifying what’s wrong with you and removing your own bias about race and inequality. Direction action – telling people and teaching what you learn.

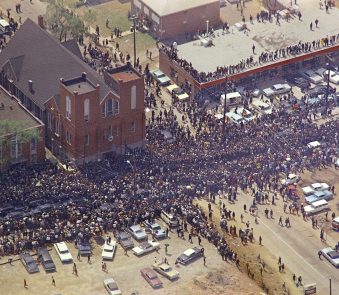

The teachings of Martin Luther King Jr. go beyond the classroom when teachers like Gonzalez take their students on field trips to the rich historical museums Atlanta has in its backyard. The Civil Rights Museum offers a 4-D lunch counter experience which Gonzalez calls “powerful” because it ties in the issues of human global rights which transition nicely into upper-level courses focusing on world history.

And at The King Center For Nonviolent Social Change, King’s sister, Dr. Christine King Farris, helped develop curriculum for teachers.

The center is partnering with the Atlanta Public School System to integrate curriculum, according to the King Center.

“The goal is to start at home and spread the integration of the curriculum around the world,” Dr. Hilda R. Tompkins, senior director of strategic education partnerships and initiatives at The King Center, said in a statement.

The Atlanta History Center took 30,289 students on tours in 2017 of their most popular exhibits, “Fight for Your Rights: The History of African American Progress.”

“Fight for Your Rights is a tour we’ve done for the last four to five years to create empathy by putting the kids in role of a civil rights activists. They participate in freedom rides, sit-ins or meet the local activist John Wesley Dobbs where the kids are put in a place to know what it means to be a freedom fighter,” said Kevin Edmiston, the Atlanta History Center’s Manager of Education Programs.

“The civil rights movement wasn’t just about Dr. King or Rosa Parks, but also students and John Wesley Dobbs, who was a mail clerk. They were ordinary people who put their lives and careers on the line. We also talk about John Lewis and how he was a college kid who became a freedom fighter. What is important is these folks weren’t much older than the kids themselves.”

Parents may feel lucky to have teachers like Gonzalez and Beach going above and beyond to engage their students and celebrate not only King but the many historical and present day figures who were affected by his actions.

“The times we’re living in right now, kids are much more in tune and engaged. People are speaking out a lot more about a lot of different things so there’s a way to always make connections and Dr. King is a great way to move through that,” Gonzalez said.