Martin Luther King Jr.’s Right-Hand Adviser: Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy

In My List

In My List

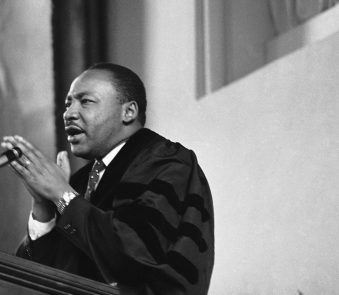

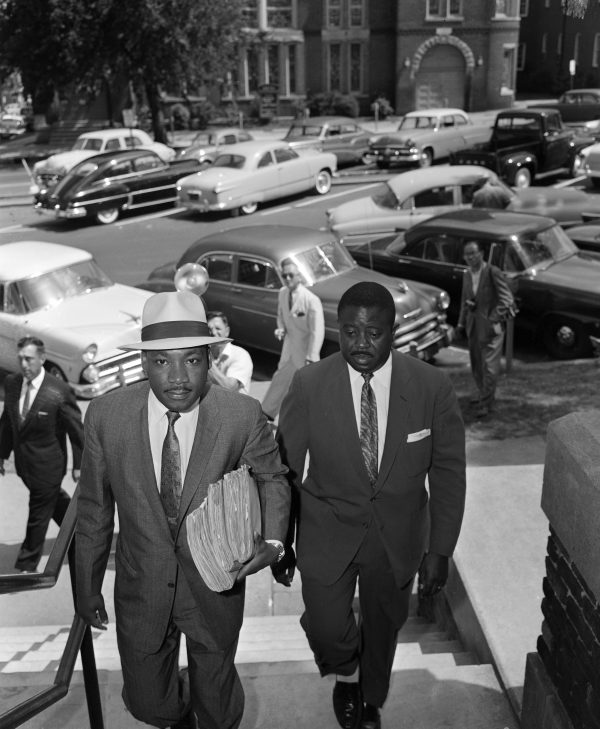

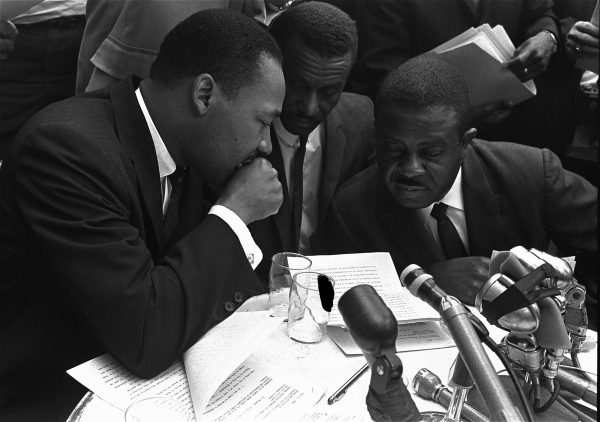

The Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr.’s close adviser and “best friend,” was one of the most influential leaders during the civil rights movement.

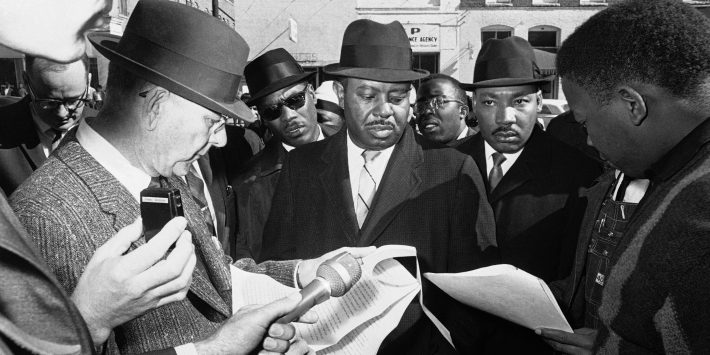

The pair worked side-by-side for more than a decade organizing the Montgomery bus boycotts, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the Poor People’s Campaign and numerous other civil rights protests throughout the South.

“I tell students all the time … I say, ‘Don’t mention Martin Luther King Jr. without mentioning Ralph David Abernathy. Dr. King was our leader, but Ralph David Abernathy was his equal partner,” Tyrone Brooks, former Georgia House District 55 representative, said. He became involved with the SCLC at 15 years old, and Brooks worked with Abernathy as an SCLC volunteer to a full-time employee.

Abernathy, one of 12 children born in rural Linden, Alabama in 1926, served in World War II, studied at Alabama State College, received his graduate degree at Atlanta University and worked as a Baptist minister before he started pushing for civil rights.

He met King in his 20s after hearing him minister at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta.

“Even then I could tell he was a man with a special gift from God,” Abernathy wrote in his 1989 book, “And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: An Autobiography.”

From there, the pair’s families became close and the leaders realized they shared united civil rights goals.

“As Martin expounded philosophy, I saw its practical applications on the local level … ,” Abernathy wrote in his autobiography.

Throughout Abernathy’s life, he cared deeply about the Civil Rights Movement. Brooks, who has worked for decades on the Moore’s Ford Movement, said Abernathy was prepared to die for the cause. Going to jail and having his house bombed didn’t faze him.

“Dr. Abernathy always said, ‘We all will die one day. When we die, we should die doing something good,’” Brooks said. “Dr. Abernathy always instilled in us that death was imminent, that you could be shot down or you could be run over. You could be bombed.”

After Rosa Parks was arrested by Montgomery, Alabama, for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger, Abernathy and King teamed up to create the Montgomery Improvement Association that coordinated the bus boycotts resulting in Alabama bus desegregation in 1956.

“I think when God put them together to lead the modern day revolution and Abernathy decided he wanted to take a back seat to his best friend in the world, Martin Luther King Jr., from that moment on … we saw one of the greatest revolutions to ever hit the world,” Brooks said. “Not only did it transform America, but it really changed the world.”

A year later, Abernathy co-founded the SCLC with King and other leaders in 1957. The group went on to engage in the March on Washington where King delivered his famous “I Have A Dream Speech” that led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

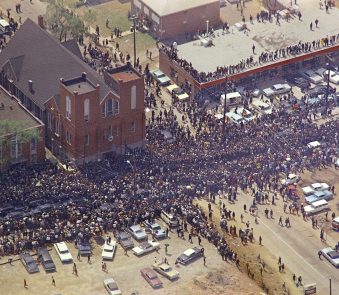

When King died in 1968, Abernathy carried the torch and continued their initiatives as SCLC’s president. He led the Poor People’s Campaign march on Washington, D.C. in May 1968 that brought out thousands and the creation of Resurrection City for the end of poverty.

He later settled down in Atlanta, where he ran for office, preached at the West Hunter Street Baptist Church and created the Foundation for Economic Enterprises Development, which helped black people with their finances.

Abernathy fought tirelessly for the civil rights movement up until he died of a heart attack at the age of 64 on April 17, 1990 in Atlanta.

Correction: A previous version of this story said the SCLC was founded in 1967, it has been corrected to reflect the organization was founded in 1957.