The Life And Legacy Of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

In My List

In My List

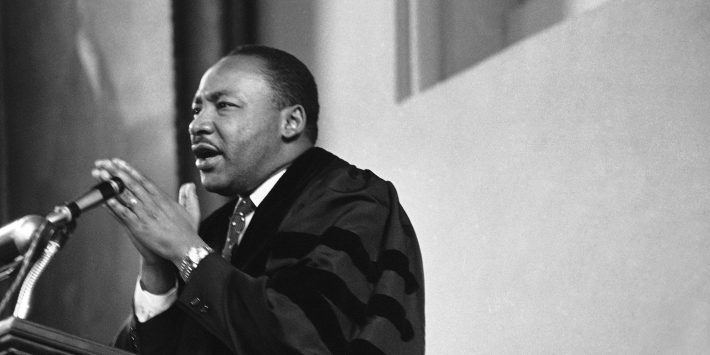

Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) was a social justice activist, Baptist minister and author who most visibly led the American civil rights movement from December 1955 to April 1968, when he was assassinated. A native of Atlanta, Georgia, he fought to end racial segregation through nonviolent protests in the South and other areas. As head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he promoted social, political and economic equality among people of diverse backgrounds. His leadership and inspirational rhetoric, including the “I Have a Dream” speech, have been credited with playing major roles in the passage of landmark civil and voting rights legislation in the 1960s. In 1964, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

On January 15, 1929, King was born Michael Luther King Jr. in Atlanta to the Rev. Michael Luther King Sr. and Alberta Williams King. The senior King later changed both his and his son’s first name to Martin, according to historian Taylor Branch. King was the second of three children, who included older sister Christine and younger brother Alfred Daniel known as A.D.

The family lived in a two-story Queen Anne home at 501 Auburn Ave. in a middle-class neighborhood known as Sweet Auburn. Though its businesses, churches and entertainment venues were racially segregated, Sweet Auburn was a bustling cultural and commercial hub of African-American life unrivaled elsewhere in the South, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

King graduated from Booker T. Washington High School in 1944. At age 19, he earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Morehouse College, an all-male historically black college in Atlanta. It was the alma mater of his father and maternal grandfather, A.D. Williams, who pastored Ebenezer Baptist Church.

At Morehouse, King became fascinated with the concept of nonviolent resistance after reading the works of philosopher Henry David Thoreau, according to “The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.” It was also advocated by Benjamin Mays, a Baptist minister and admirer of Indian independence leader Mahatma Gandhi. As Morehouse president, Mays influenced generations of activists. In his autobiography, King credited his father and Mays for inspiring him to enter the ministry.

“I felt a sense of responsibility which I could not escape,” King said.

In college, King joined the Intercollegiate Council, an interracial student discussion group that regularly met at nearby Emory University, according to The King Center. King’s growing interest in social justice was apparent in an Aug. 6, 1946, letter to the editor of the Atlanta Constitution, in which he wrote that blacks are “entitled to the basic rights and opportunities of American citizens.”

A few months before graduating in June 1948, King was ordained a Baptist minister by his father, who succeeded his father-in-law as pastor at Ebenezer. In 1951, King earned a divinity degree at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. He then studied theology at Boston University, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1955. While in graduate school he became a member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the nation’s oldest black intercollegiate Greek-lettered fraternity.

In Boston, King met another southerner, Coretta Scott, a music student. Raised a Methodist, Scott said she initially hesitated at the thought of becoming the wife of a shouting Baptist preacher, especially one she considered boyish looking and too short in stature. However, she was impressed with the determined man she came to know.

“The more I was with Martin, the less I could find not to like about him,” she wrote in her autobiography, “My Life, My Love, My Legacy.”

They later married at her home in rural Alabama on June 18, 1953. The couple eventually had four children: Yolanda, Martin III, Dexter and Bernice. In 1954, 25-year-old King and his family moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where he was called to pastor Dexter Avenue Baptist Church.

Following the arrest of Rose Parks for refusing to give her bus seat to a white passenger, Montgomery’s black community leaders appointed King to lead the boycott of the city’s segregated buses in December 1955. It lasted 381 days, during which time King’s home was bombed but his family was not injured. The successful conclusion of the boycott, which came when Alabama’s bus segregation laws were declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, placed King in the national spotlight.

“Idealists would say afterward that King’s gifts made him the obvious choice,” historian Taylor Branch wrote of King’s selection as leader in his book, “Parting the Waters.” “Realists would scoff at this, saying King was not very well known, and that his chief asset was lack of debts or enemies.”

In 1957, a group of black ministers formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to fight for racial equality and elected King president of the organization. From this period King emerged as the nation’s most prominent civil rights leader. He traveled around the nation and to other countries to address racial inequity, met with elected officials and in 1958 published his first book, “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story.” By this time, King had returned to Atlanta as assistant pastor at Ebenezer.

King’s nonviolent demonstrations against legalized segregation in cities like Birmingham, Alabama, attracted more followers to the civil rights movement, which in turn increased violent resistance by local authorities, which shined more media attention to the freedom struggle. Many moderate whites who supported gradual integration did not agree with King’s direct tactics, as well as some middle-class blacks, according to historians. In response, King penned an open letter widely published as “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” after he and fellow activist Ralph Abernathy were arrested in April 1963.

“We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability,” King wrote. “It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of men willing to be coworkers with God, and without this hard work time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation.”

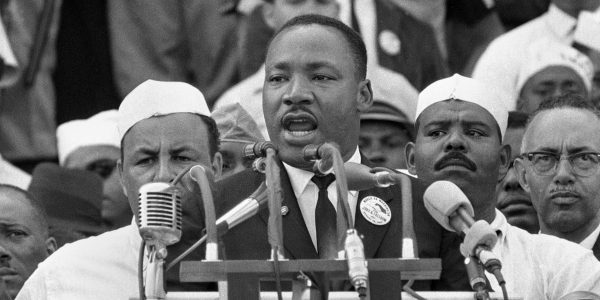

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was organized on August 28, 1963, in part to pressure President John F. Kennedy to take greater action in support of civil rights. King headlined the event in which he called for an end to racism in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered to a crowd of 250,000 people, according to a National Park Service estimate.

“We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation,” said King as he stood on the granite steps of the Lincoln Memorial. “So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

Wornie Reed, a sociology and Africana studies professor at Virginia Tech, said he listened to the speech from the crowd. He first met King at Dexter Avenue church during the bus boycott as an Alabama State College student and became so enamored, he said, that he traveled to hear him speak more than 30 times and attended his funeral.

“I used to say to myself as I would listen to him speak or preach, ‘Wait until the world hears this man,’ not realizing how fast that was already happening,” Reed recalled in an email. “He was mesmerizing, and there was a definite aura about him.”

Historian David Garrow, author of “Bearing the Cross,” called the “I Have a Dream” speech the “rhetorical achievement of a lifetime, the clarion call that conveyed the moral power of the movement’s cause to the millions who had watched the live national network coverage.”

In January 1964, Time magazine placed King on its cover as “Man of the Year.” On Dec. 10, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize at a ceremony in Oslo, Norway. “I accept this award today with an abiding faith in America and an audacious faith in the future of mankind,” King said in his acceptance speech.

In between the two achievements, during the summer of 1964, Congress passed and President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act, which prohibited voting discrimination, was passed.

Along with countless other activists, King’s efforts, including a mass march in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery that drew national and international attention to the bloody violence unleashed on the marchers by state and local authorities, are widely recognized for drawing support to the civil rights movement. In April 1965, four months before Johnson signed it into law, a Gallup opinion poll found 76 percent of Americans favored proposed equal rights voting legislation.

However, King’s popularity waned as he shifted his focus to economic inequality, spoke out against the Vietnam War and a younger and more militant generation of black activists called for speedier changes in society, according to Garrow.

On April 4, 1968, King was assassinated by gunshot at the Lorraine Motel during a visit to support striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. He was 39 years old. An obituary in The New York Times said that to millions of black Americans, King was their “voice of anguish, their eloquence in humiliation, their battle cry for human dignity.”

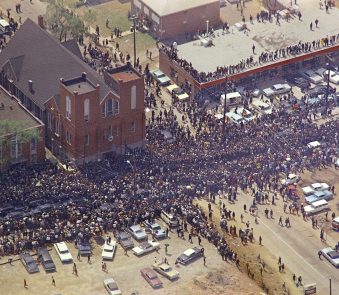

On April 9, thousands lined the streets of Atlanta to observe King’s funeral procession between private and public services at Ebenezer and Morehouse, respectively. Prominent leaders, foreign dignitaries, entertainers and fellow activists attended the funeral. Mays eulogized his former student and famed gospel singer, Mahalia Jackson, sang King’s reportedly favorite hymn, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.”

“I remember the funeral as a sad and somber occasion,” said Reed, the King admirer. “I also thought I sensed a degree of resoluteness among participants, something that suggested we would carry on despite King’s death.”

Years after burial at a local black cemetery, King’s body was exhumed and laid to rest at the King Center in Atlanta, alongside his widow, Coretta, who died in 2006. Today, King is the only non-president to be honored with a national holiday and one of the few non-presidents with a memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

In his book, “The Inconvenient Hero,” scholar and activist Vincent Harding reflected on the popular perception of King as a colorblind idealist and what he described as the more radical prophet he transitioned into during the turbulent late 1960s.

“For his greatness may rest not so much in the dream, but in his willingness to continue to hope, to struggle, to develop new vision, to call others to a new America, right in the midst of nightmares, despair, and brutally broken bodies,” said Harding.